Paperowl

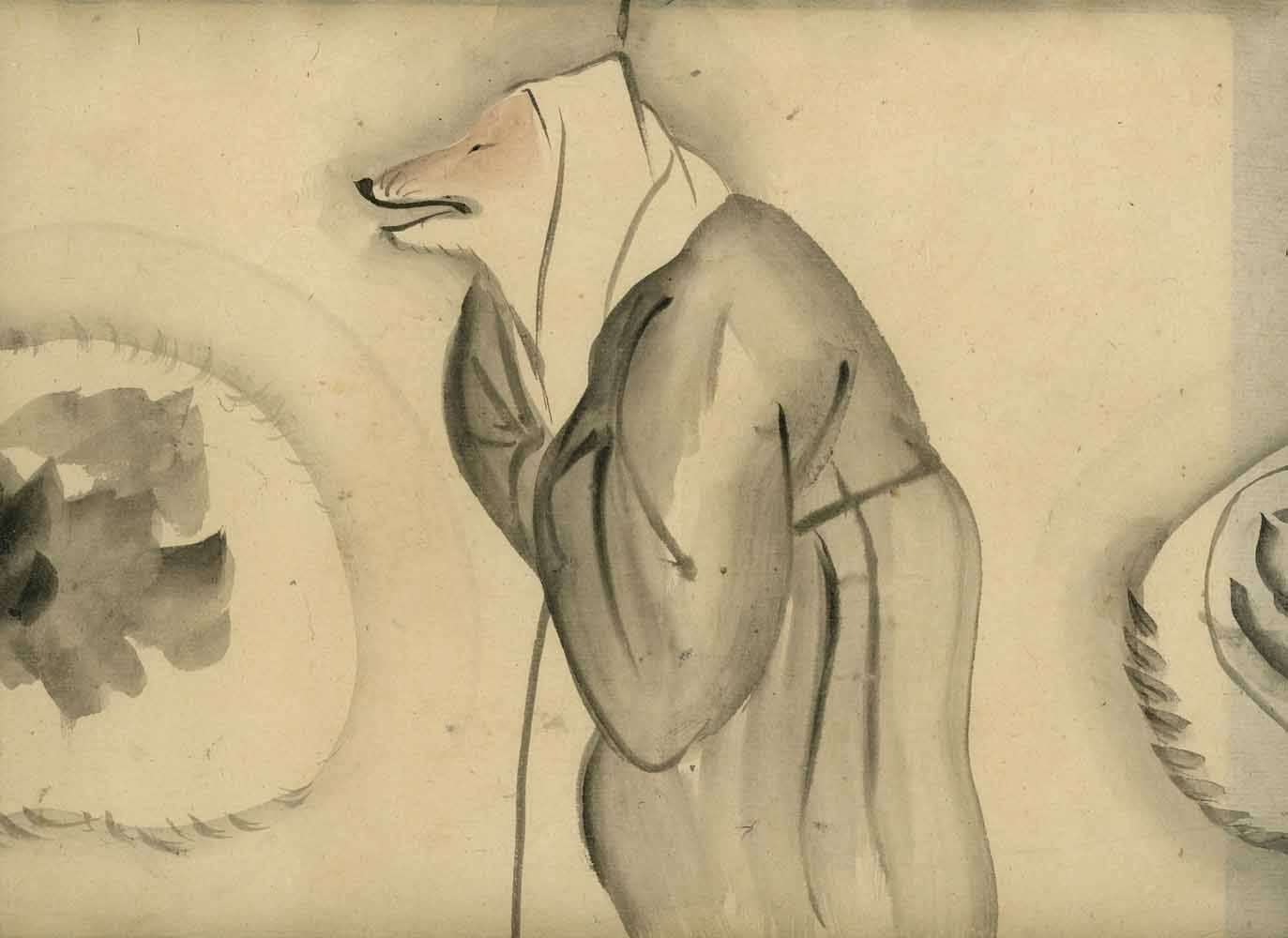

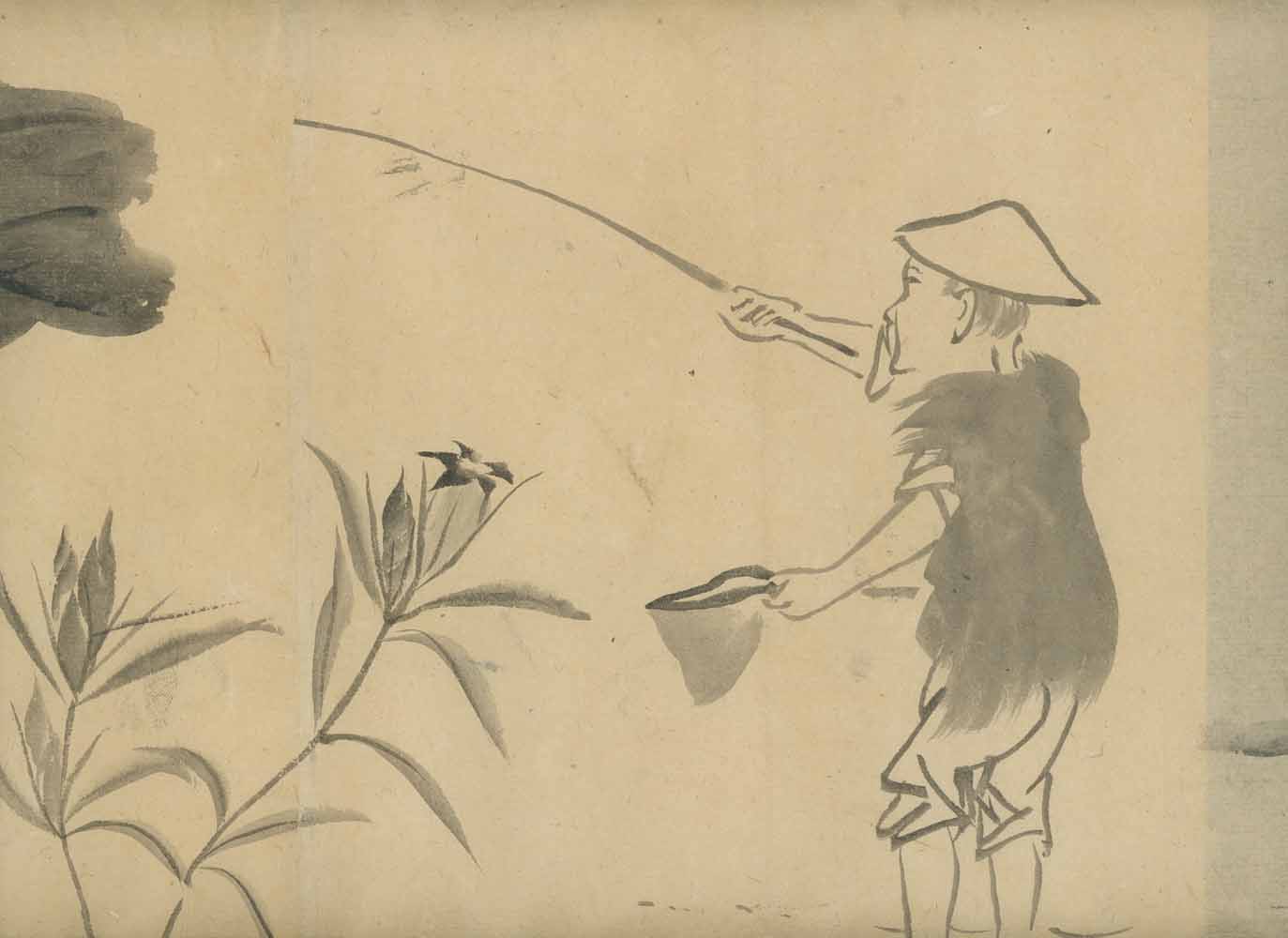

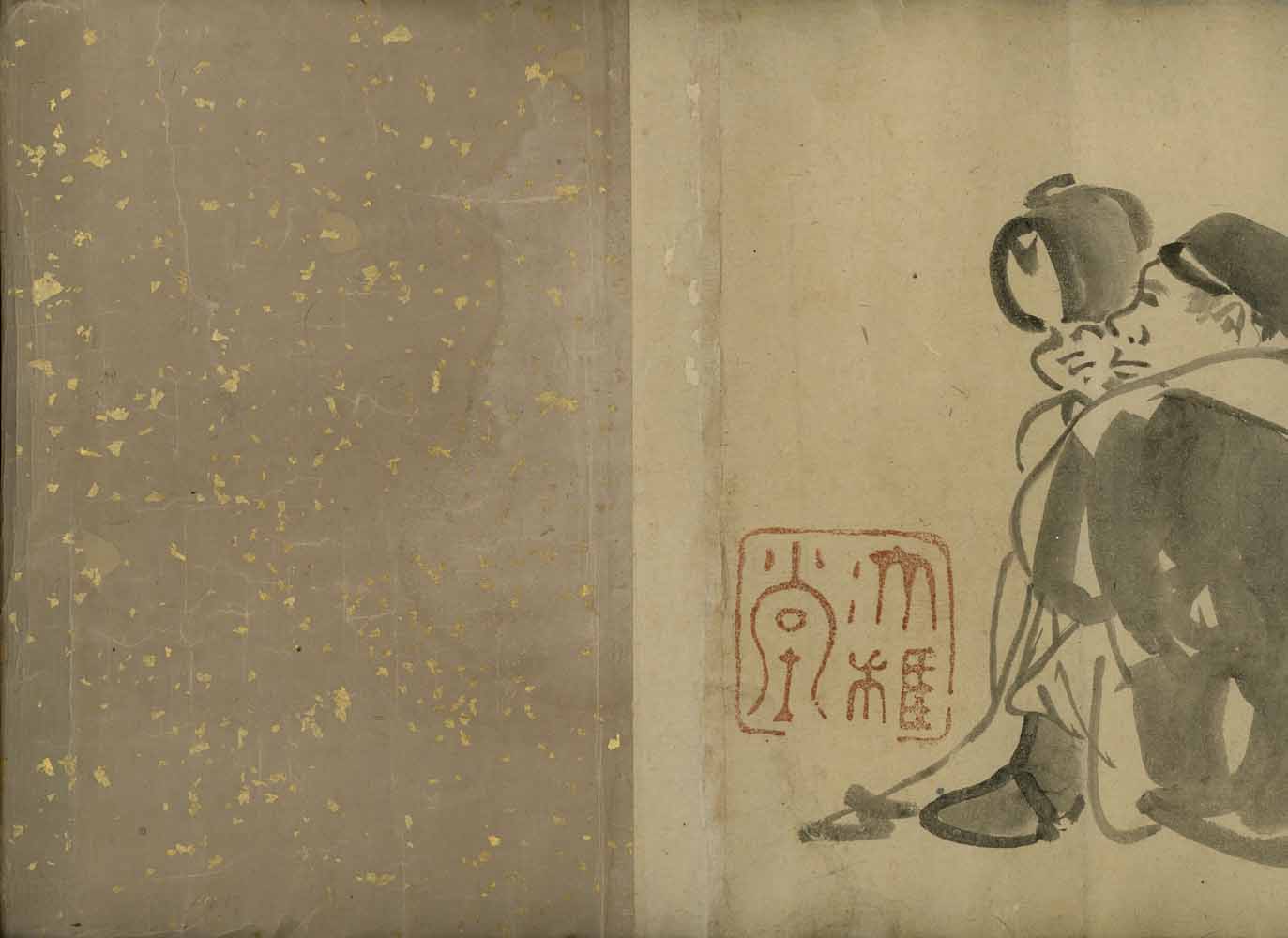

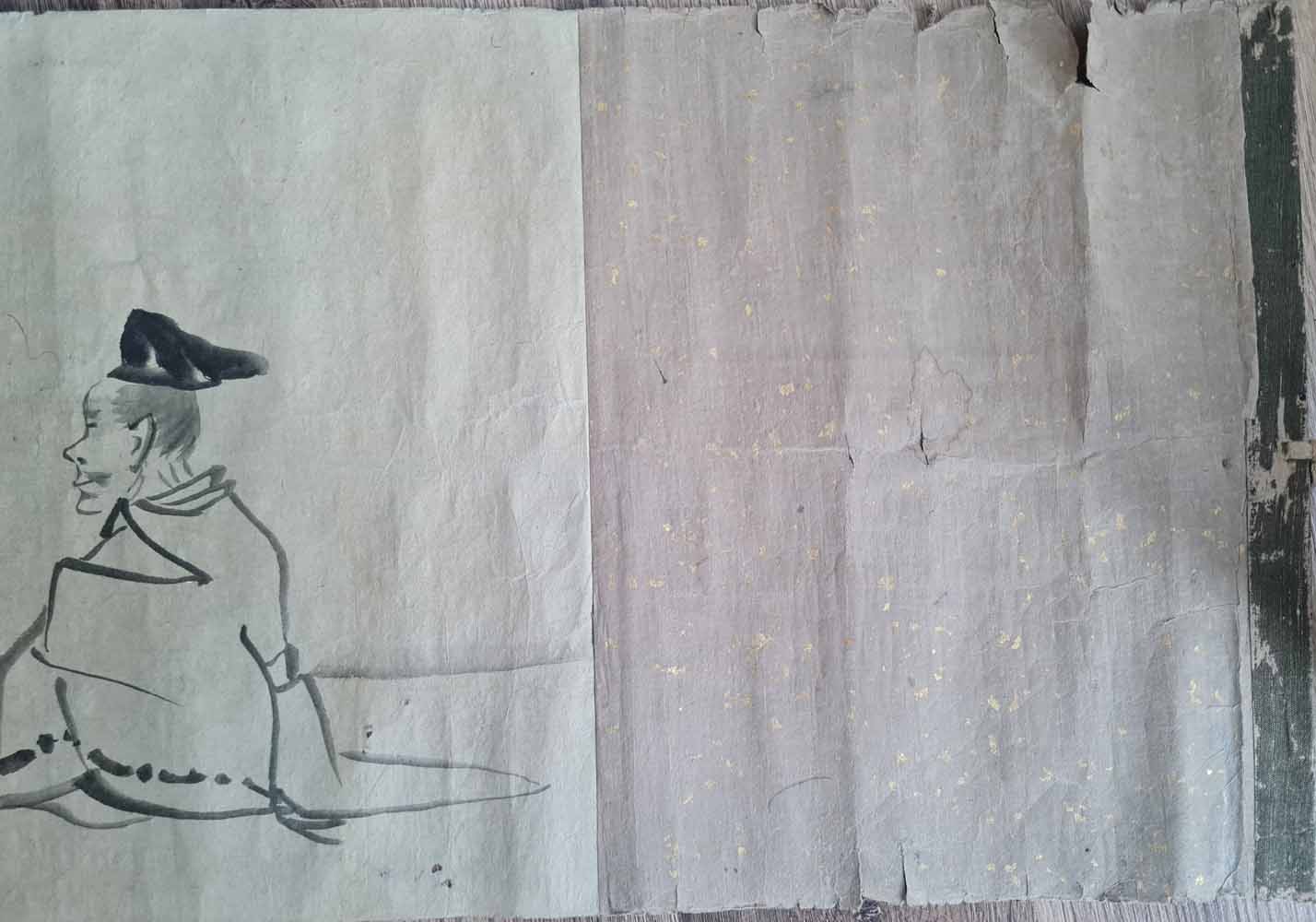

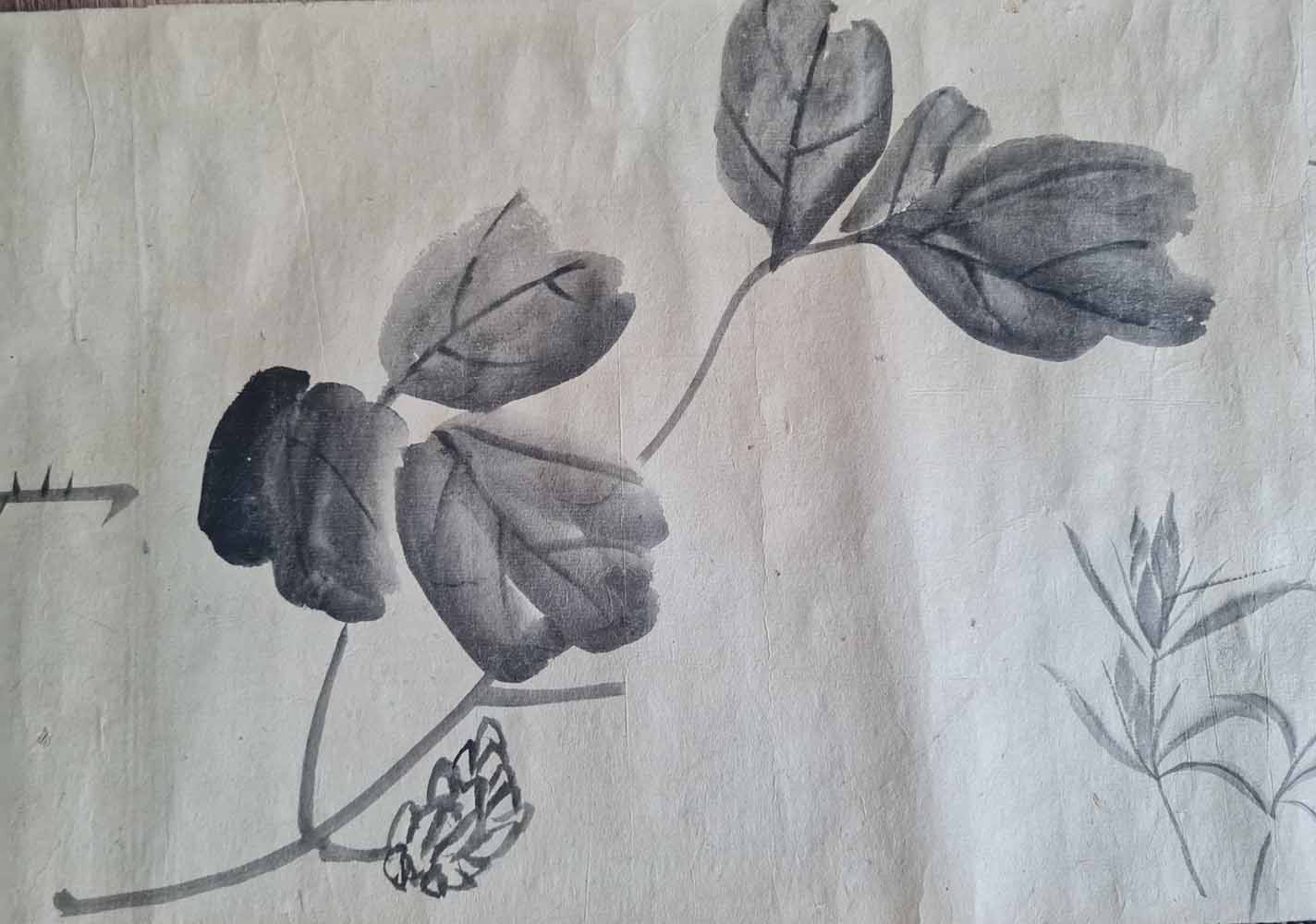

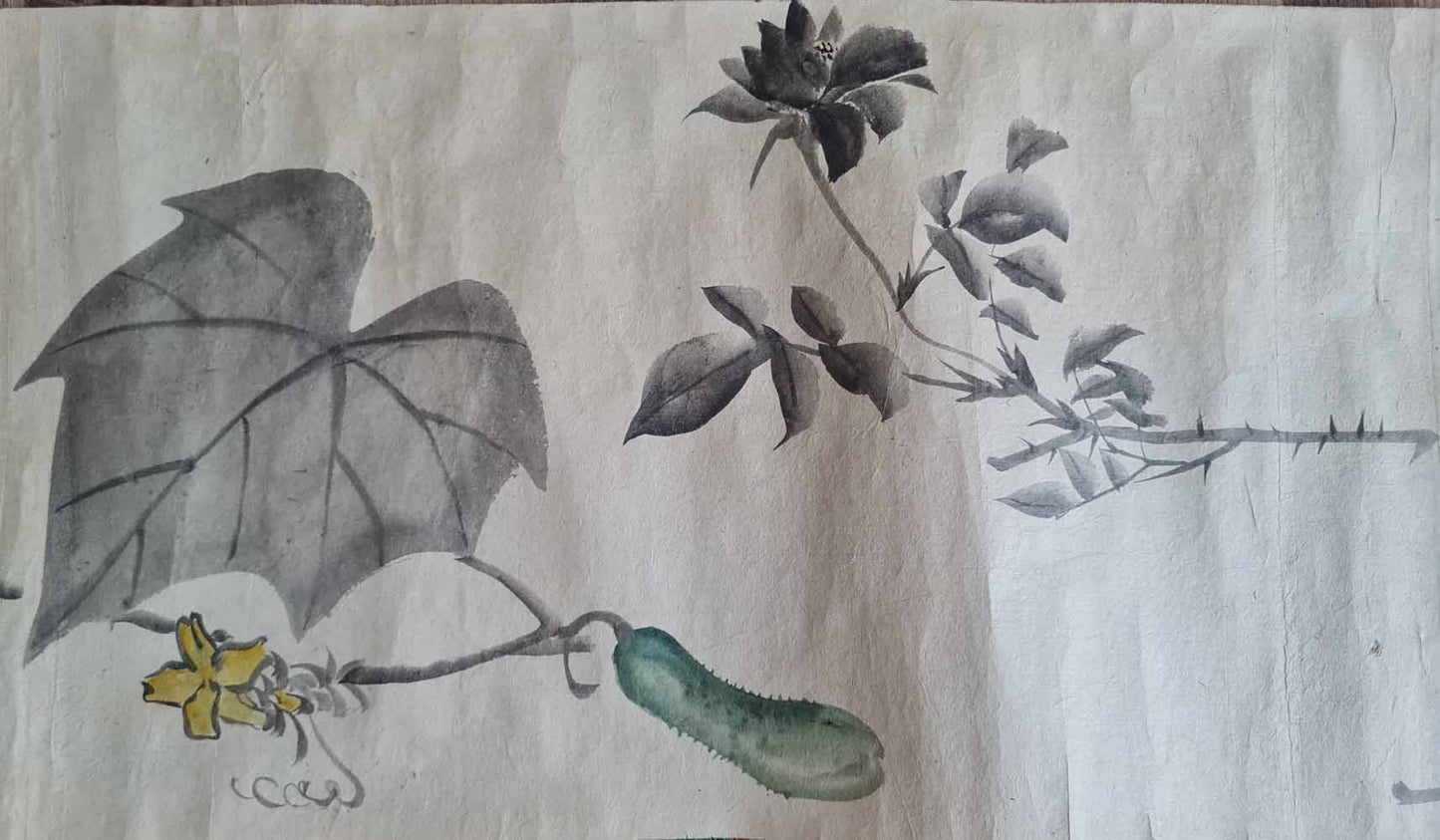

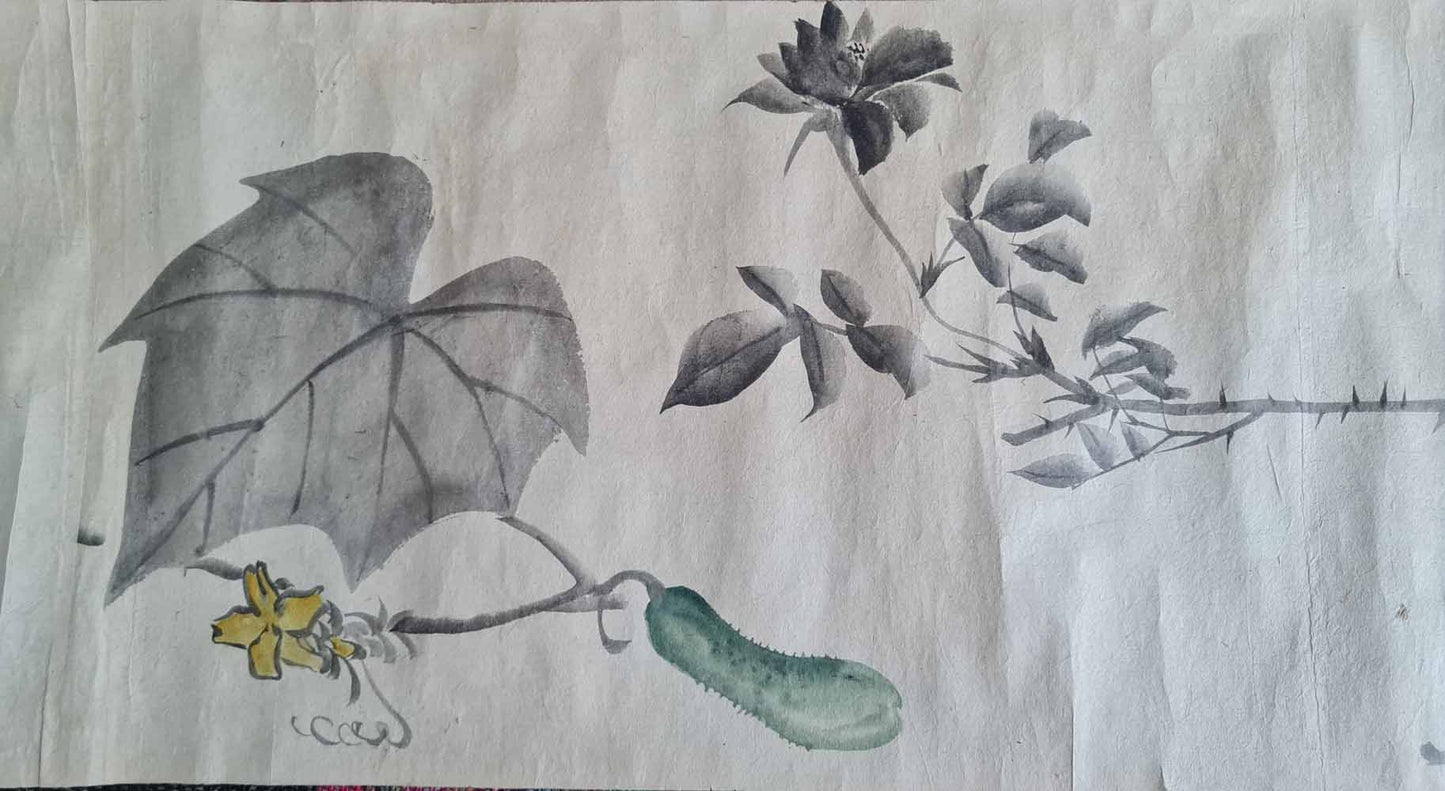

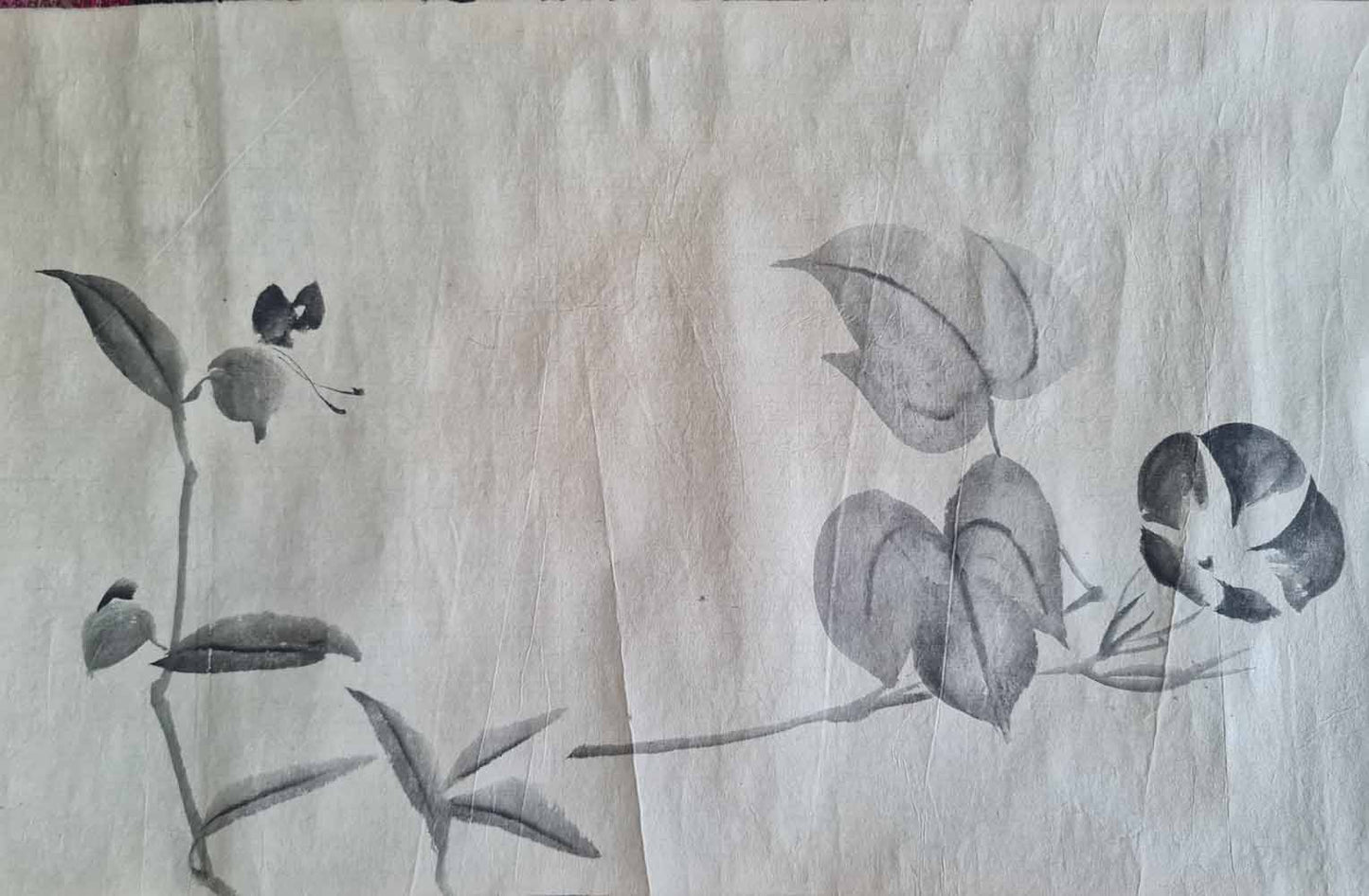

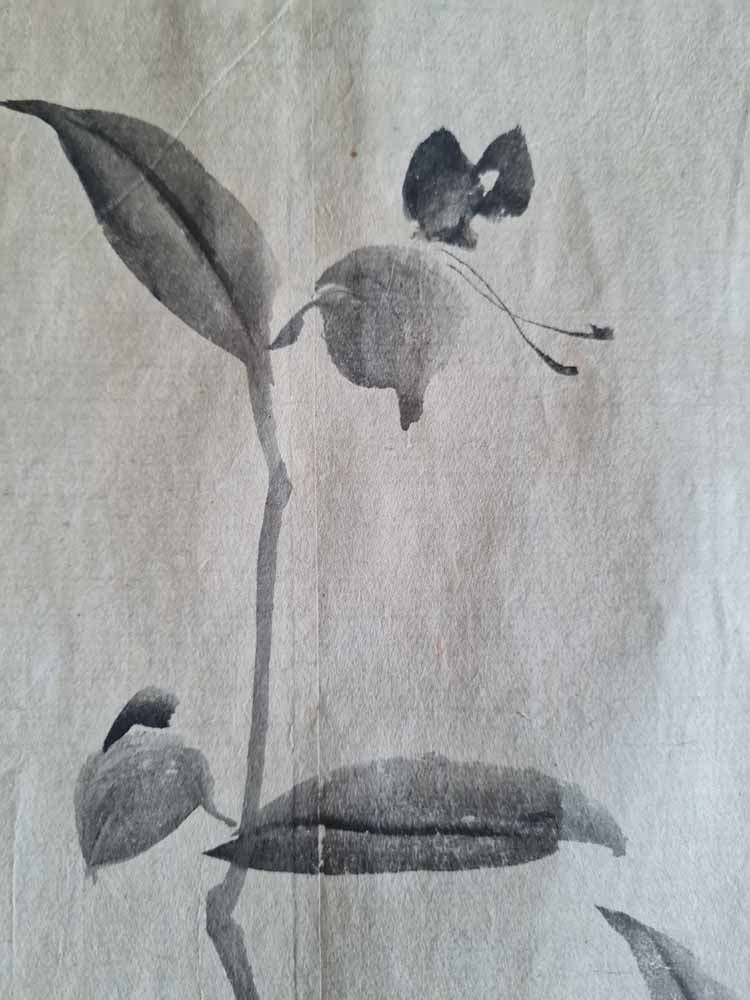

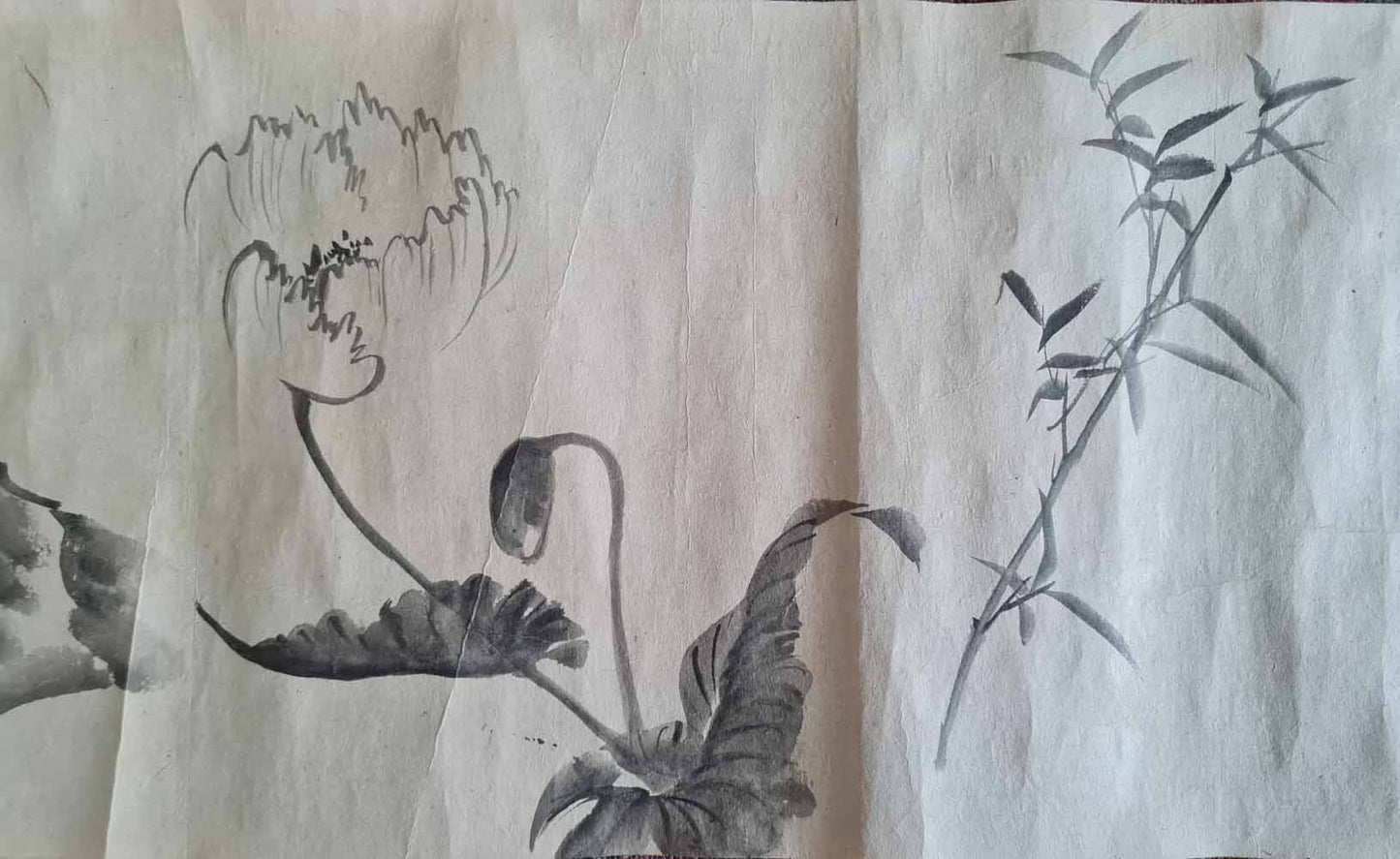

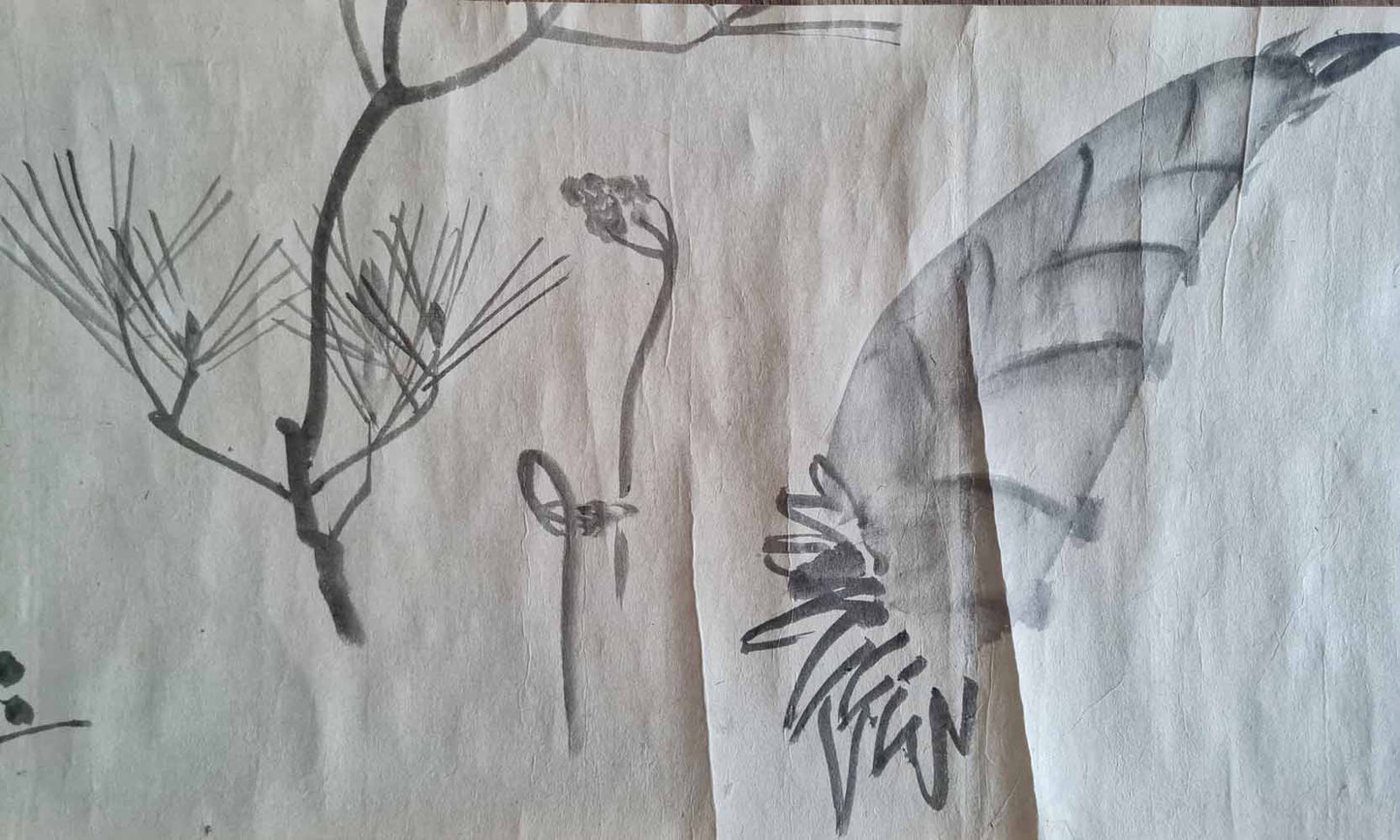

Emakimono scroll 絵巻 - 池大雅 Ike no Taiga, ca. 1760

Emakimono scroll 絵巻 - 池大雅 Ike no Taiga, ca. 1760

Couldn't load pickup availability

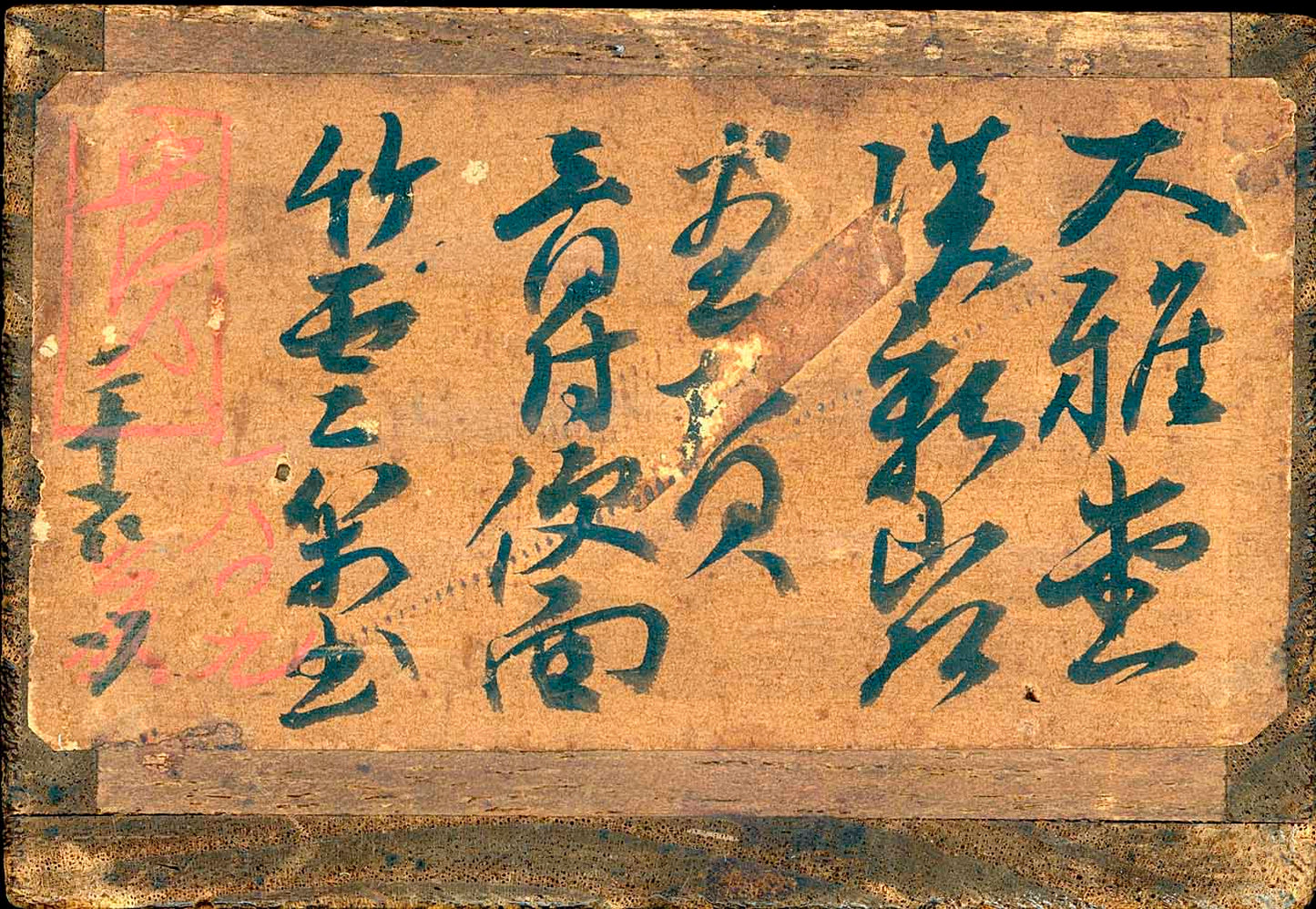

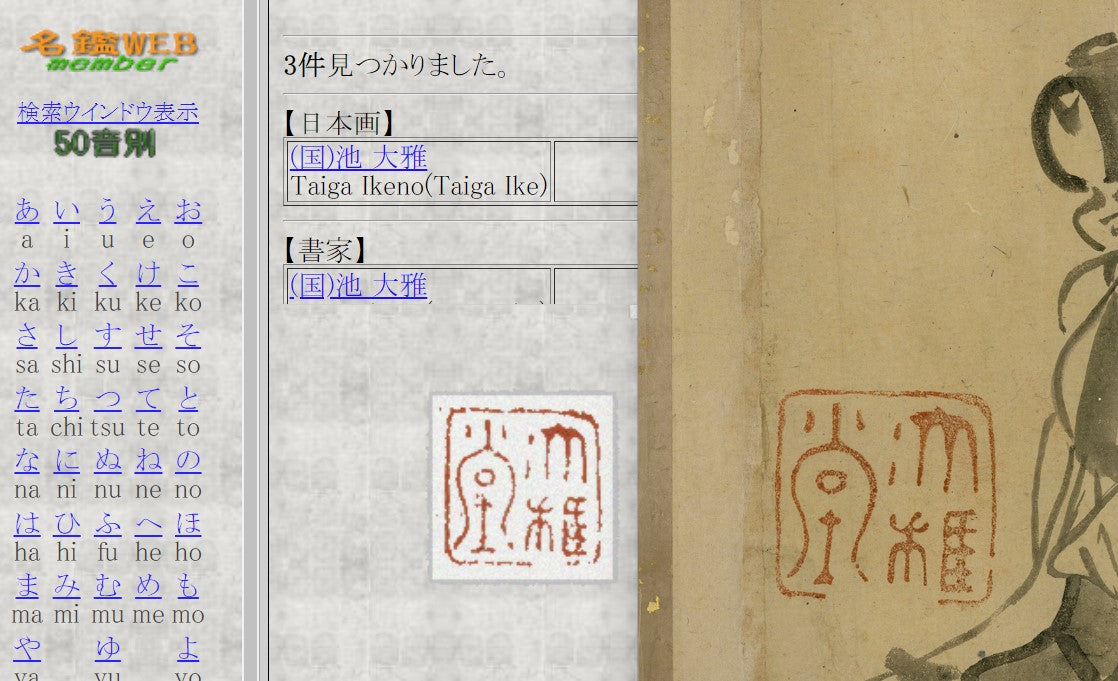

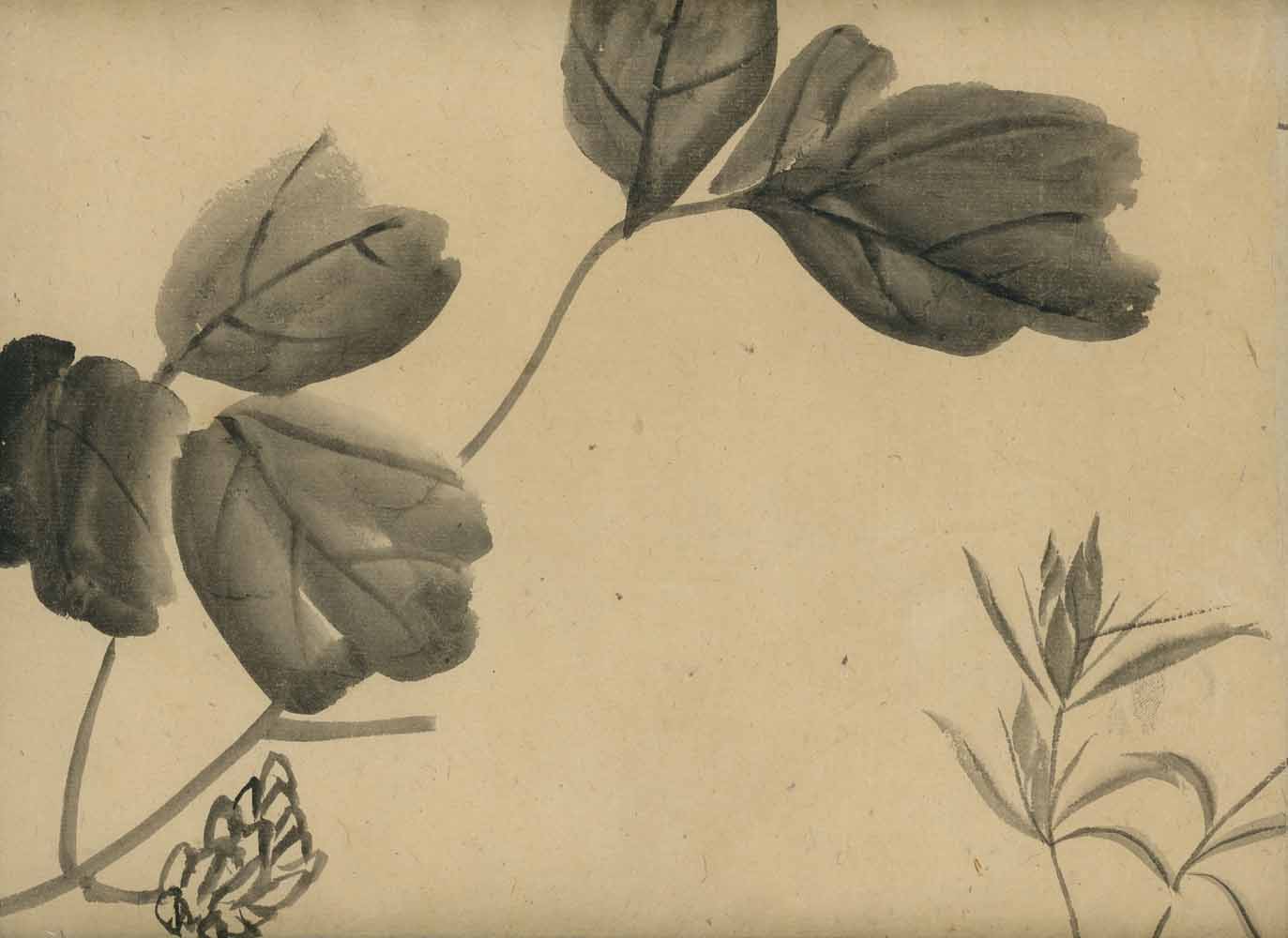

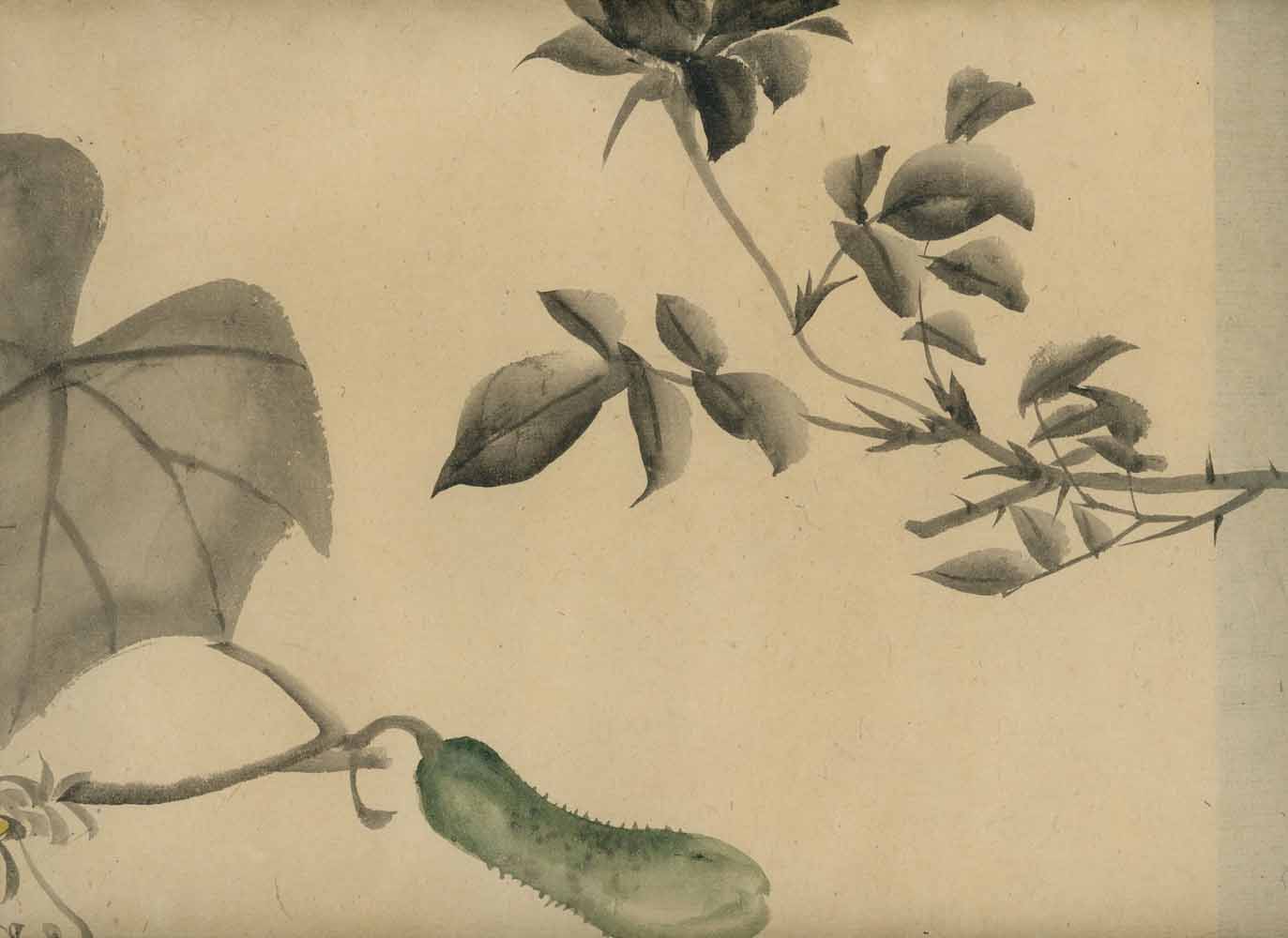

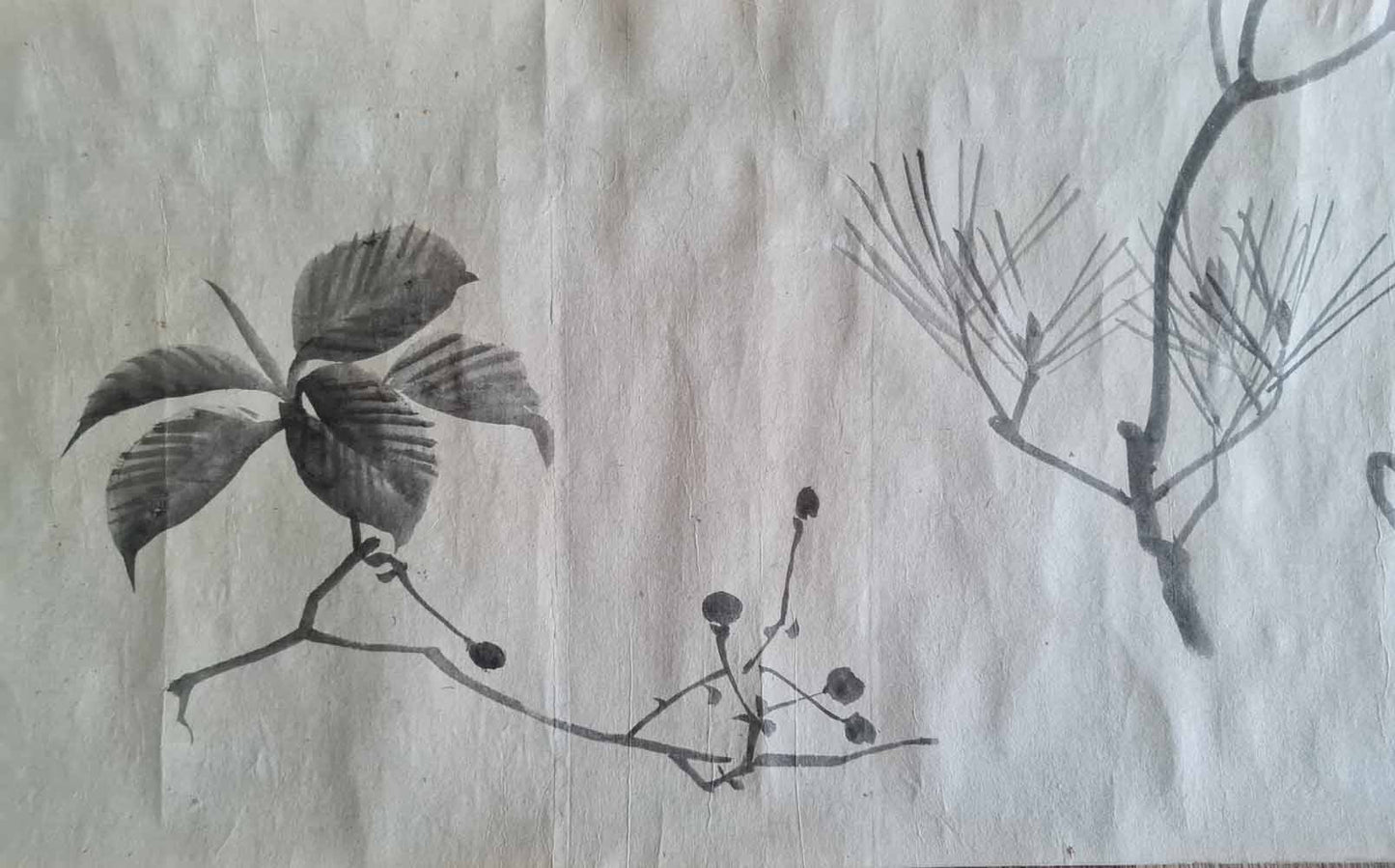

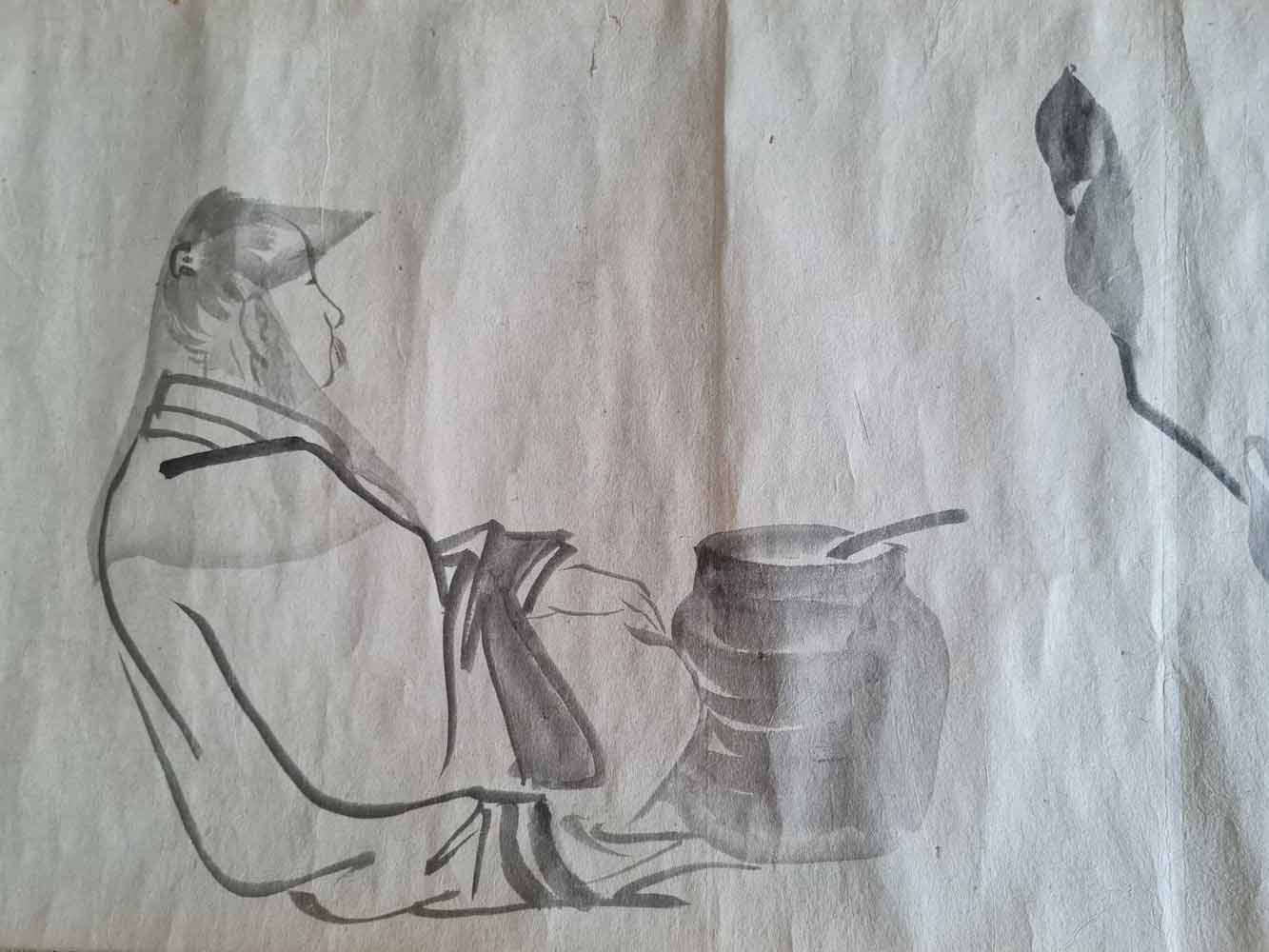

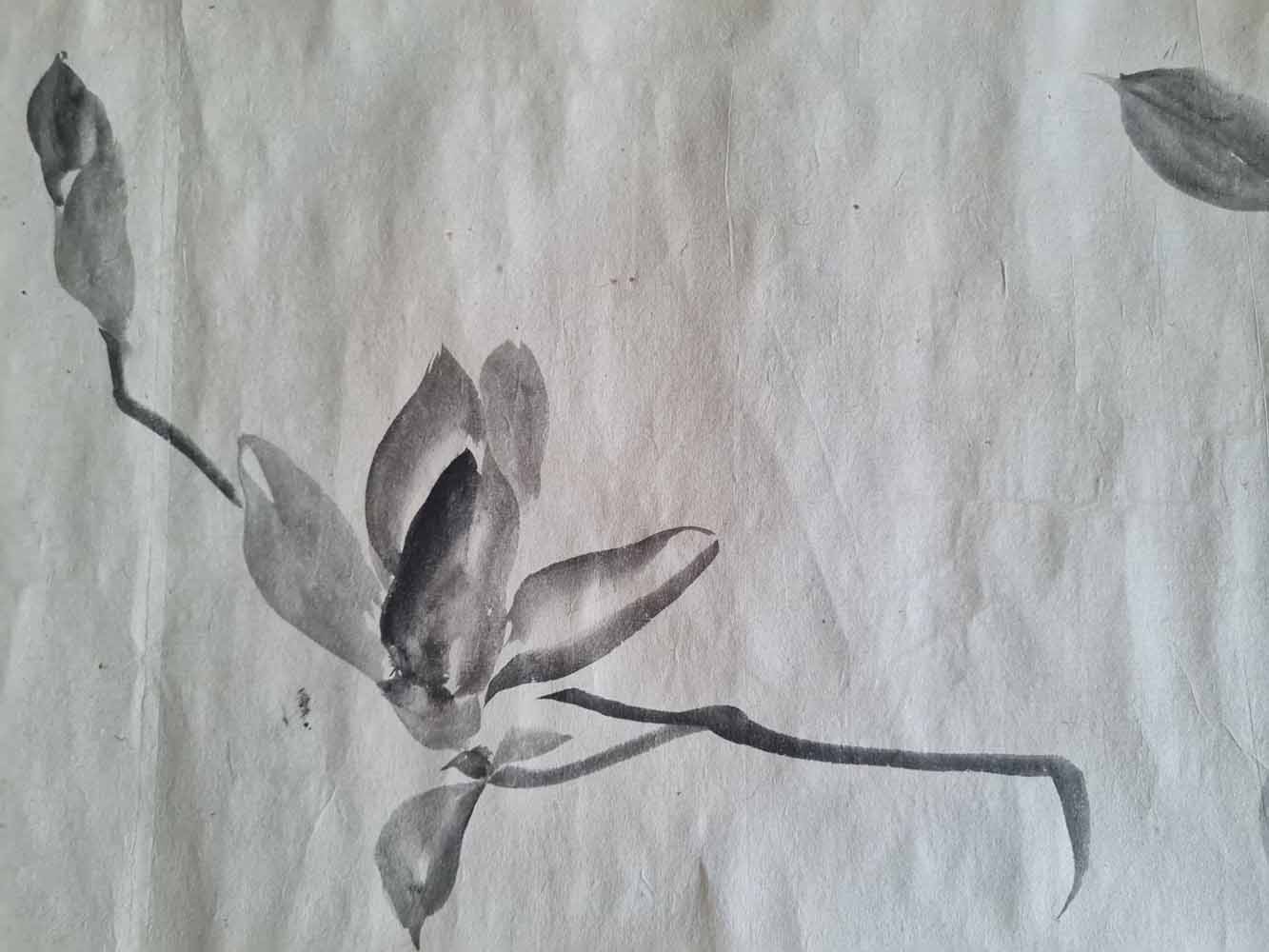

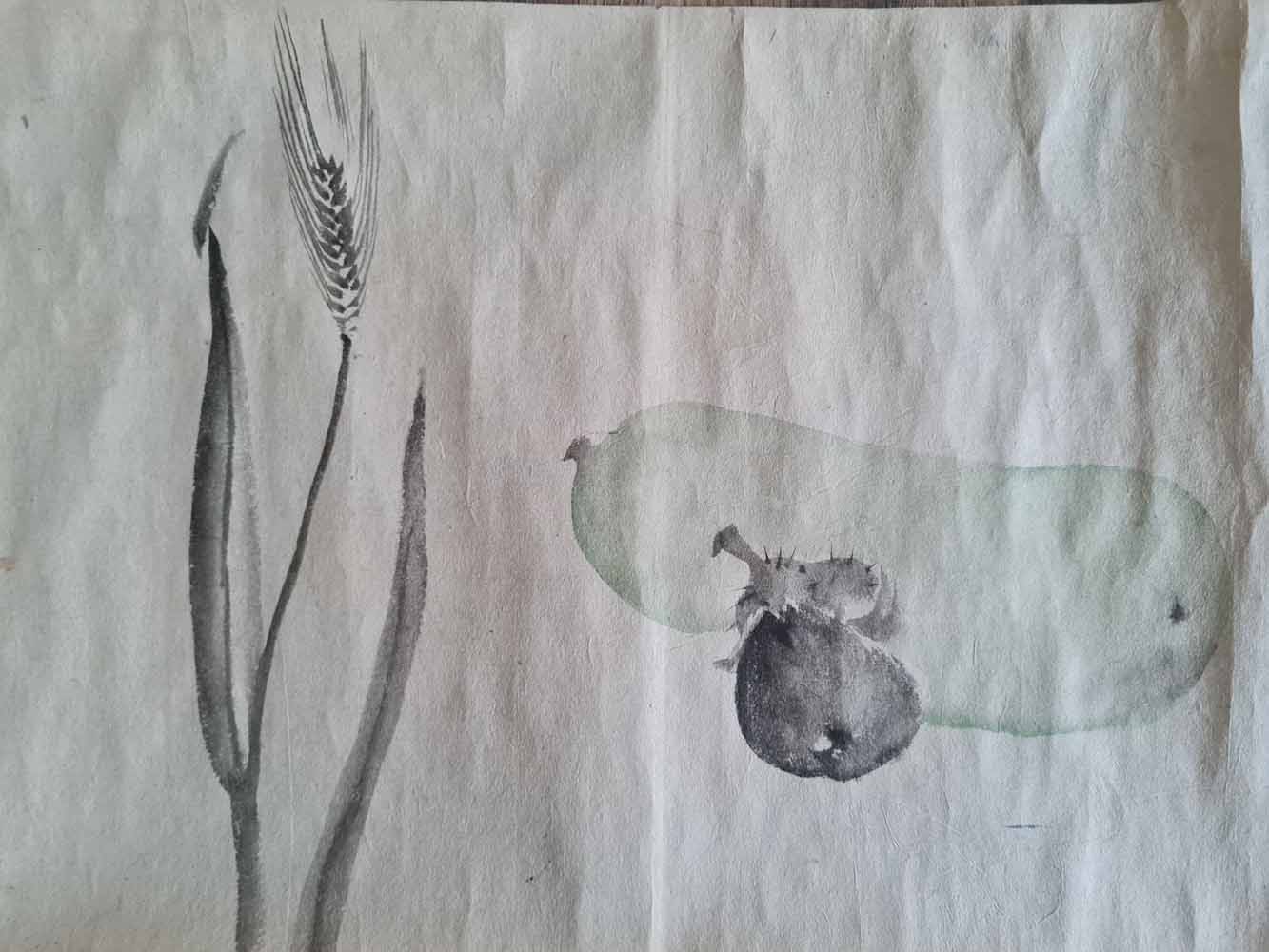

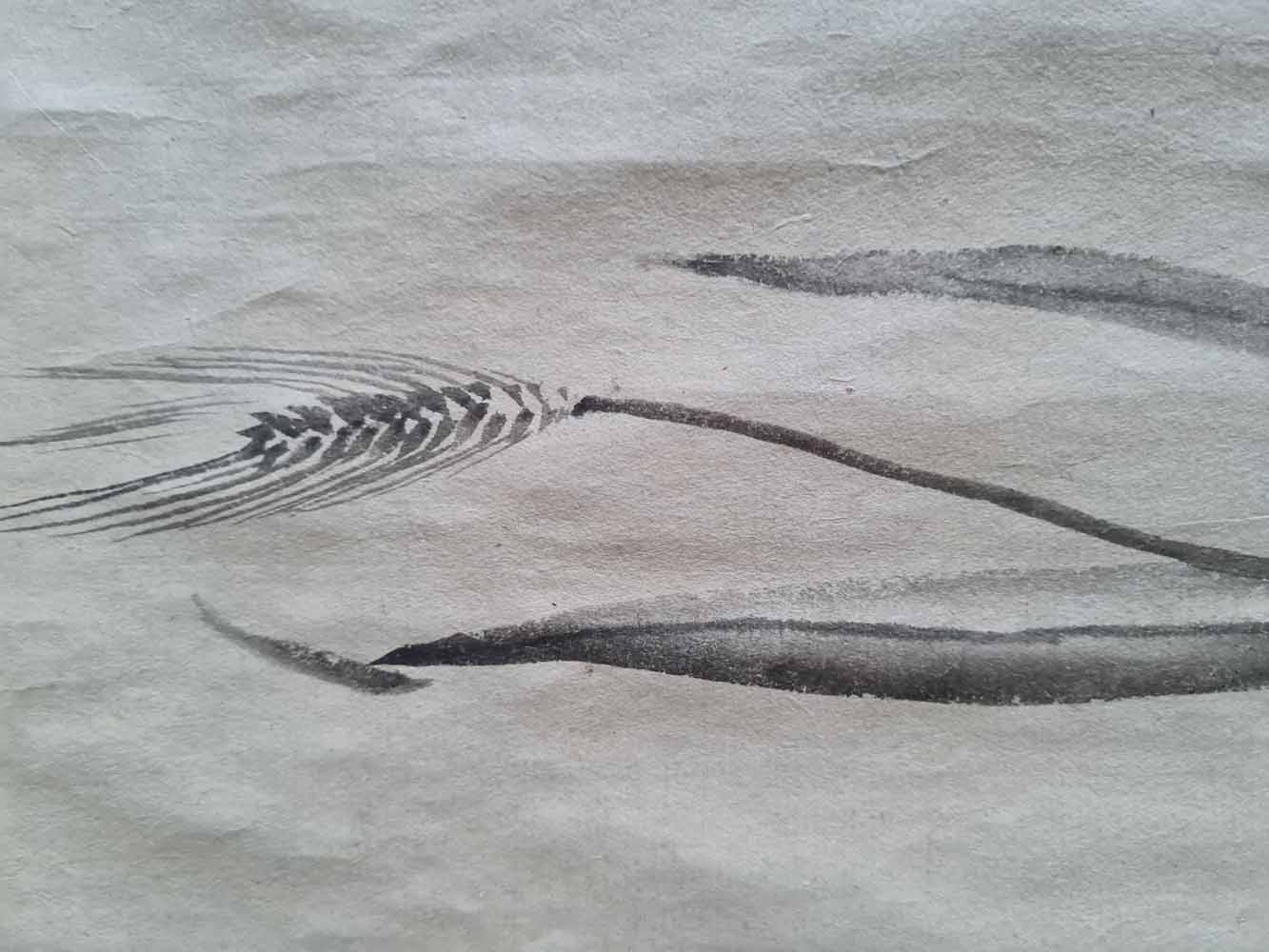

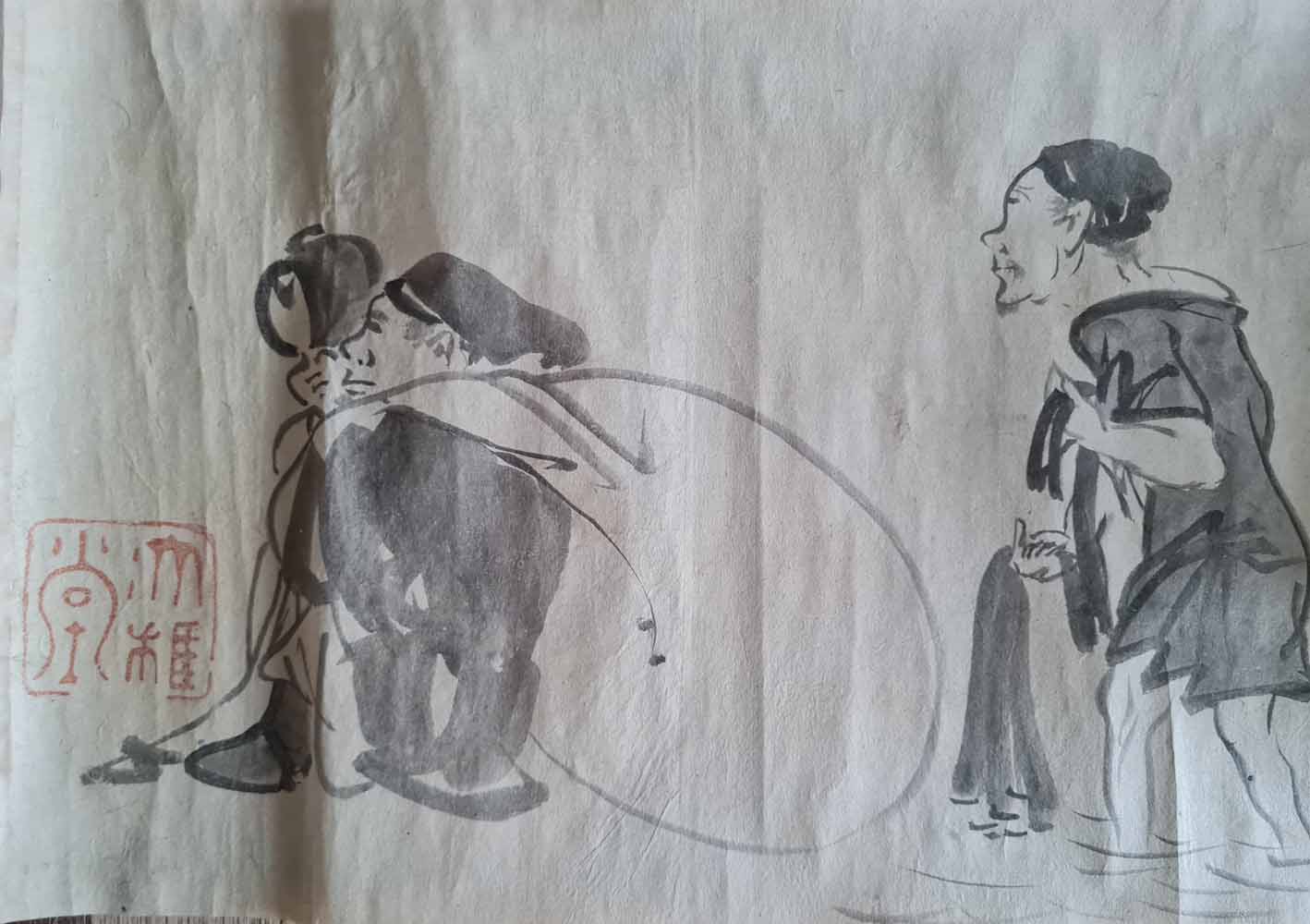

A wonderful emakimono scroll with the seal of Ike Taiga, size 25 x 540 cm, gold leaf at the beginning and ending, no foxing. The seal matches the one in databases (see photo)

Among the new styles of painting to make their appearance in eighteenth-century Japan, the Literati or Nanga School was destined to enjoy a particularly widespread popularity. At the dawn of that century, the number of Japanese known to have applied their talents to this Chinese-inspired mode of painting could literally be counted on the fingers of one hand. By its close, the host of Nanga painters, both professional and amateur, probably numbered in the thousands. The central figure in the transformation and popularization of the imported art form was Ike (no) Taiga 池大雅 (1723-76), one of Japan's most talented, imaginative, and prolific painters, as well as a versatile and innovative calligrapher. A rough estimate of the number of surviving paintings and calligraphical works by or attributed to Taiga would yield a figure of around 2,000. Building on the groundwork laid by his three predecessors, Gion Nankai (1677-1751), Yanagisawa Kien (1706?-58), and Sakaki Hyakusen (1697-1752), Taiga created a satisfying synthesis of Chinese and Japanese traditions. Besides painting traditional Literati subjects such as landscapes, "four gentlemen" plum, bamboo, orchid, and chrysanthemum), and figure paintings of paragons of Chinese culture, Taiga expanded his repertoire to include a considerably broader range of themes than most Chinese scholarpainters would have considered acceptable: figures from Japanese folklore, Buddhist and Taoist subjects, local scenery and festivals, and narrative illustrations of literary themes. Taiga's singular independence from convention is to be seen in technique as well as theme. He employed a wide variety of techniques, including simple outline drawing using both slanted and upright brush, light color or monochrome wash, elaborate heavy polychrome, haboku ("broken ink"), hatsuboku , ("splashed ink"), tarashikomi (blurring of pigments), and even finger painting (shitoga ), in addition to the formal brush vocabulary of texturizing strokes (shun) and dots (ten) used in Chinese Literati painting. He also on occasion used gold leaf and gold paint. Disinclined to ally himself formally with any of the contemporary schools of painting, Taiga, restlessly experimenting with styles and type-forms, adopted elements from a melange of sources far afield from Chinese scholars' art.

--from Ike Taiga: A Biographical Study by Melinda Takeuchi, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

Share